Yoshio Sakamoto is the Less Famous Twin of Shigeru Miyamoto who can Paint Better.

Super Metroid 3 is a 1994 Super Nintendo game designed by Japanese artist 坂本 賀勇, Yoshio Sakamoto. Yoshio Sakamoto is a rival of 宮本 茂, Shigeru Miyamoto; Creator of Mario and Zelda. Both are long time staples at Nintendo, but Miyamoto is regarded as the visionary Steve Jobs and Sakamoto is largely unknown; an artist never able to escape from the shadow of Miyamoto. Two points exemplify this: 1) Sakamoto’s games are evaluated and critiqued by how they compare to Miyamoto’s. Sakamoto’s Metroid is frequently described as a hybrid of Mario and Zelda (both Miyamoto’s creations). 2) A tertiary side character from the Mario universe designed by Miyamoto, Yoshi the dinosaur, is widely more recognized than the artist it was named after, Yoshio Sakamoto.

Super Metroid 3 is Sakamoto’s best game which received wide critical acclaim and has become a classic re-released continuously by Nintendo for the last 20 years and will likely be played in perpetuity as the history of video games becomes established as an area of cultural study. While replaying Super Metroid 3 with my children I was struck by the audacity and effectiveness of Sakamoto’s artistic design which is far superior to that of the rival Miyamoto’s, though not as original. Metroid’s creative fault is that it is deeply rooted in dogmatic science fiction whereas Miyamoto’s Mario, a game of an Italian plumber who grabs coins and mushrooms to defeat lizards is a true original creation completely unseen in our universe before; this is in essence why Sakamoto is unknown despite his robust capabilities as an artist.

Super Metroid 3 palette identifies who Sakamoto is as a person.

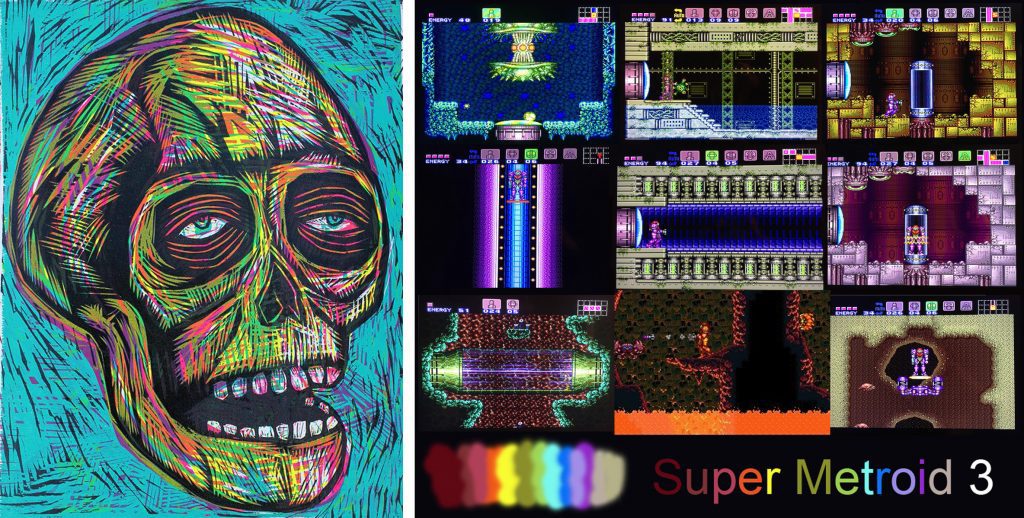

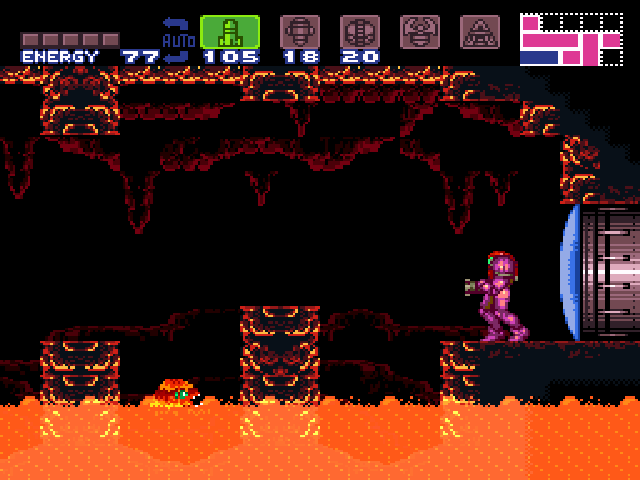

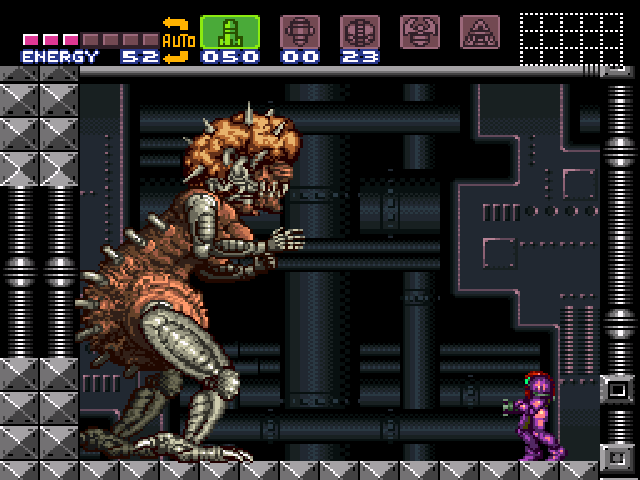

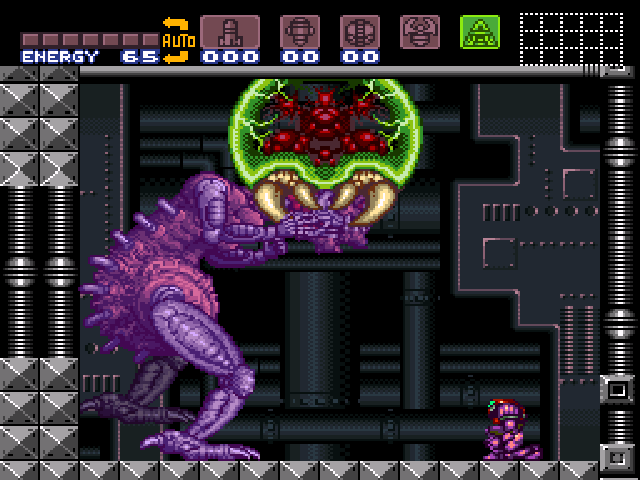

The first thing that strikes you about Sakamoto’s design is the audacity of the color pallet and the utter confidence with which it is wielded to brutal effect. The gold lining in Super Metroid 3 is its color palette. If I showed you the Super Metroid 3 palette by itself on a white background you would see this:

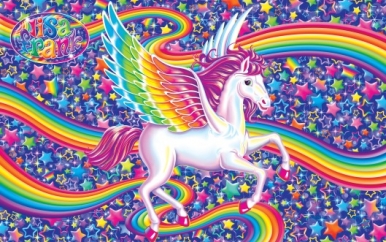

Now imagine a universe boldly painted with this palette. The first thing that would come to your mind instantly would be the cocaine filled world of the powerful American Designer queen Lisa Frank.1 Now you understand just how bold this color palette is. It is extremely rare to find artists using colors like this successfully, another good reference for effective use of palettes like this within the same genre as Lisa Frank is Sean Star Wars.

Now imagine a universe boldly painted with this palette. The first thing that would come to your mind instantly would be the cocaine filled world of the powerful American Designer queen Lisa Frank.1 Now you understand just how bold this color palette is. It is extremely rare to find artists using colors like this successfully, another good reference for effective use of palettes like this within the same genre as Lisa Frank is Sean Star Wars.

We can instinctively know the personality of an artist by the palette they use. Thus, take that same color palette and put it on a black background, burst the contrast into blinking Neon at night, make it evil, and you get Sakamoto’s Super Metroid 3.

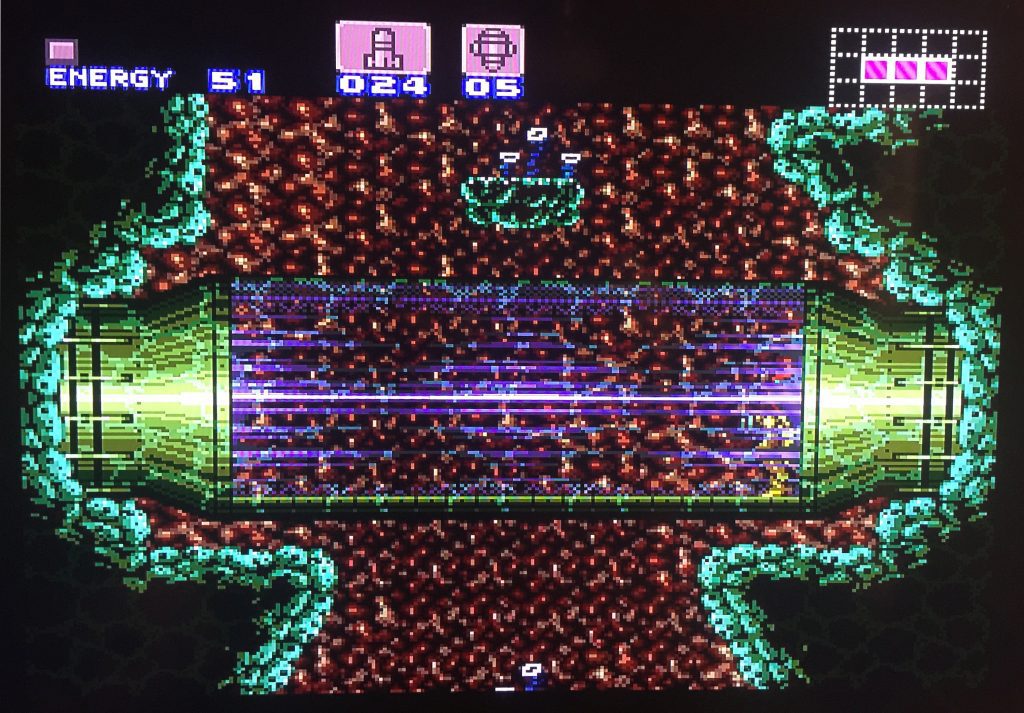

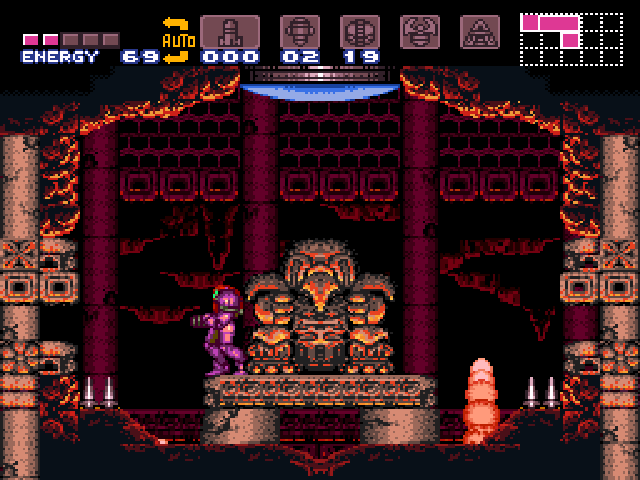

Super Metroid 3 imagery is rooted in Science Fiction Staples. What makes Super Metroid a classic, but not a landmark is that it basically reinterprets pre-established themes contributing to the cultural discussion of science fiction but failing to generate new original material. Here we see a telepod.

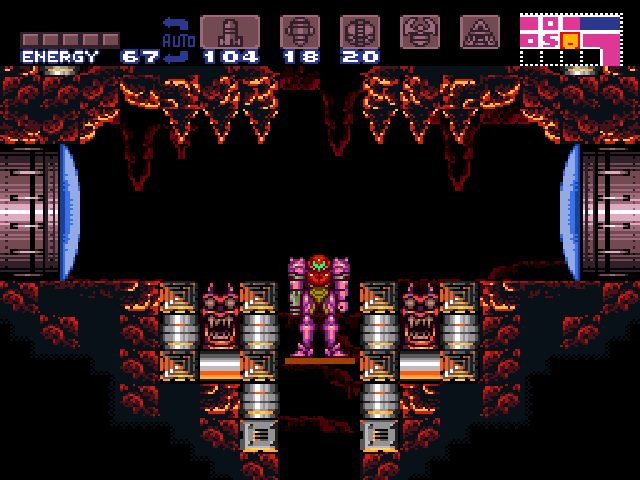

Telepods, devices that teleport people, were implied in 1944 novel Foundation by Asimov2 and made culturally ubiquitous by Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek. Roddenberry needed a cheap way to avoid filming a spaceship landing every episode thus the solution was to not have the ship land at all,3 hence “Beam me up, Scotty.” Later in 1986, David Cronenberg’s The Fly substantially modified the context of the telepod in a famous mishap creating Brundlefly, the half-human, half-fly product re-animated on the other end of a telepod contaminated by a house fly. The Super Metroid 3 telepods are significantly influenced by Cronenberg’s interpretation in that they are small individual pods of the approximate size of a person, crowned by a studded spherical top, and powered by vast thick cords that protrude like snakes.

Where Super Metroid 3 deviates from telepod generalities and contributes novelty is by emphasizing the pod as a means of data storage for reincarnation. If one is burned alive in lava or eviscerated by insectoid aliens the hero can simply be reincarnated at a local telepod to enjoy a subsequent iterative death or final victory.

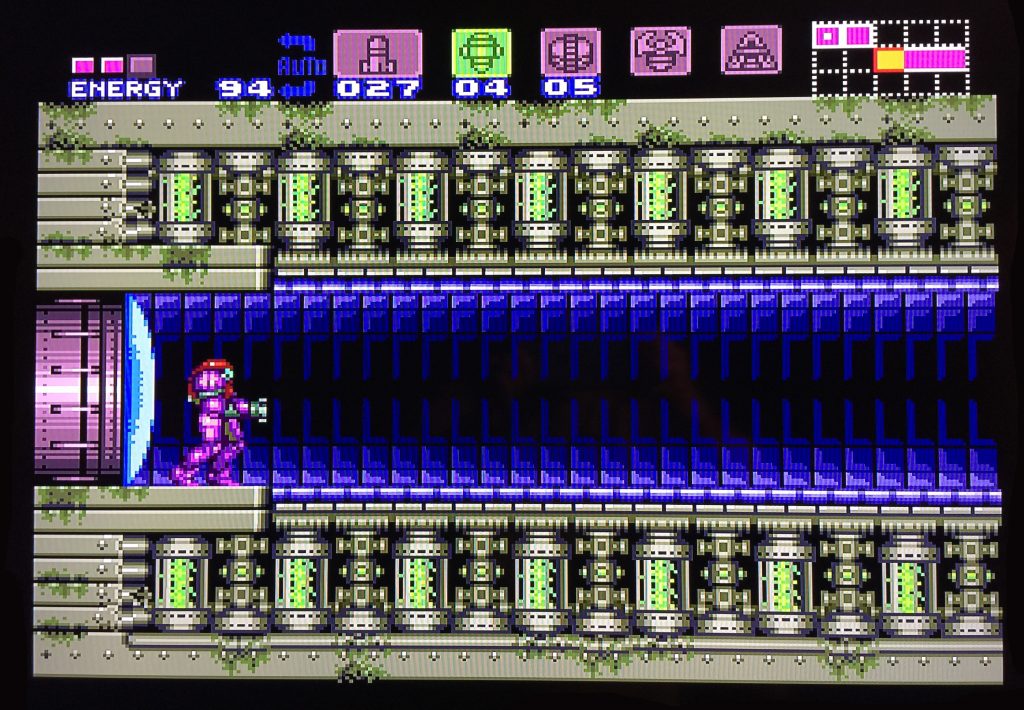

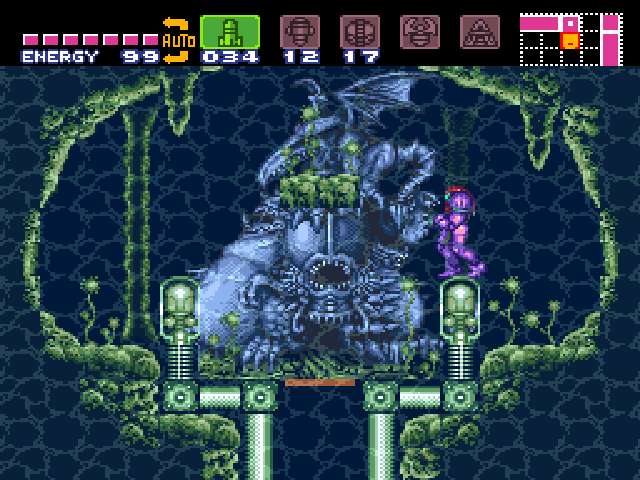

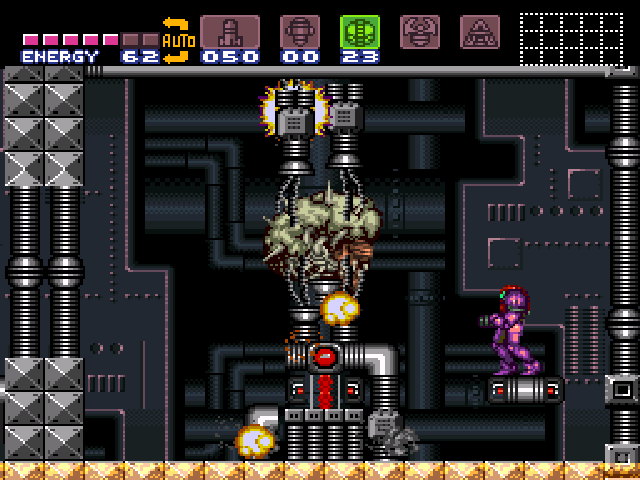

The second rote theme in Super Metroid 3 is the juxtaposition of organic with mechanical dystopia. Dystopian art emphasizes human suppression by various factors and the loss of green to the mechanical.4 Most images like this are heavily adapted from Lang’s Metropolis, 1927. What we see in Super Metroid 3 is the suppression of the mechanical by the rapid onset and growth of the bionic. Such art emphasizes organic curvatures in contrast to the stiffness of the mechanical. See above a beautiful neon tube encapsulated by organic curving rocks, themselves in toto assuming a mushroom body type reproductive figure.

There is beauty in Sakamoto’s Metroid, but every key image traces to Ridley Scott’s Alien (Designed by HR Giger).5 Giger himself is essentially a reinterpretation of themes from Alfred Kubin and Dali. Thus the greatest images within the game are not novel, but re-interpretations of Giger’s creations envisioned in a novel 16-bit color palette. Ridley Scott’s latest, Prometheus, is worth a second look after replaying and analyzing Super Metroid 3.

References:

1 Donahue, L. Unicorns, Rainbows, and Cocaine: The Rise and Fall of Lisa Frank. Jezebel (2013).

2 Prucher, J. The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction. (2006).

3 Krauss, L. M. Beam Me Up an Einstein, Scotty. Wired (1995).

4 Wall, L. D. Dystopia in the Arts. (2011).

5 Retro Gamer Team. The Making Of Super Metroid. (2014).